Almost three weeks ago, terrorists from Hamas launched an attack on Israeli citizens in southern Israel. For several days thereafter, fighting escalated as Israel fought back. And the more than two hundred people who were kidnapped during the initial attack continue to be held as hostages in Gaza.

This conflict has the potential to become a much larger battle with several other states involved (Iran, Egypt, the United States just to name few). While we don’t expect it to grow into a broader conflict, we recognize that we are also not military experts, so we think it prudent to construct portfolios that prepare for the unexpected.

We maintain investments in defense companies Lockheed Martin and Huntington Ingalls for precisely this reason (not to mention our “flight to safety” investments in U.S. Treasuries and gold).

At BCWM, we have been concerned about the potential for greater regionalized conflicts due to the changing landscape of the world’s energy supplies.

Up until a little over a decade ago, global consumers of energy have pretty much been at the mercy of the whims of despotic rulers in the Middle East. If those whims caused an oil “shortage,” the price of oil shot up.

Not anymore. Oil producers figured out how to extract fossil fuels from shale rocks deep underground using a process called “fracking.” The United States, which has a lot of these shale formations, became so proficient at fracking that we quickly became energy independent . . . which would seem to be nothing but good.

And it is mostly very good.

But the unintended consequence of being energy independent is that the U.S. no longer has the incentive to police the hot spots of the world . . . hot spots that used to threaten our ability to access billions of barrels of oil every day.

As we mentioned four years ago, a less diligent global police force leads to more conflicts. In the last 20 months alone, Russia invaded Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Armenia became embroiled in a violent clash, there seems to be the constant threat of China invading Taiwan, and Hamas led the attack on Israel . . .

Aside from the horrific toll these conflicts have taken on human lives, there are many other direct costs to the fighting: increased military spending, damage to property and infrastructure, the loss of productivity.

Another cost of the heightened unrest is a decrease in global trade.

An entire generation of younger Americans has grown up in an era of relative global peace (two of its members write these commentaries). They have benefited from the level of global trade made possible in large part by American navies. For them, the vast majority of consumer products they’ve owned carry “Made in China” labels. It was rare that an item sported the “Made in USA” tag.

That’s changing.

The next several generations will have a somewhat different experience. Pre-COVID, American businesses were already being pressured to reduce their dealings with China as trade tensions with our largest rival intensified. Then came the pandemic, causing severe supply-chain disruptions for an uncomfortable amount of time. Business leaders realized that cheap foreign labor and lax environmental regulations found abroad didn’t sufficiently compensate them for the risks in accessing their goods. They began looking to reduce their reliance on geopolitical rivals.

Thanks to the shale revolution, cheap energy in the United States has allowed for a more cost-effective production of goods at home. That energy price advantage, as well as a new appreciation for national security as a component of economic safety, has led to more and more “re-shoring” and “friend-shoring.”

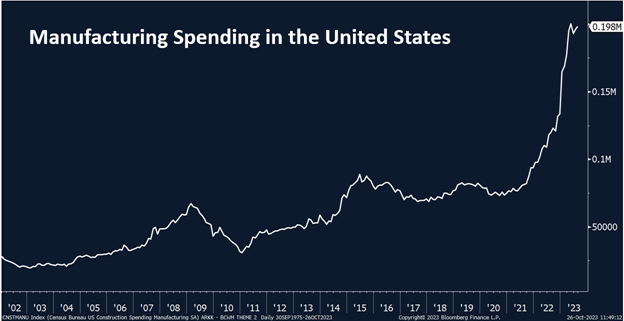

Consequently, the U.S. has seen industrial construction spending almost triple in the last 18 months.

. . . and during that time, China lost its position as our largest trading partner. That title now belongs to Mexico.

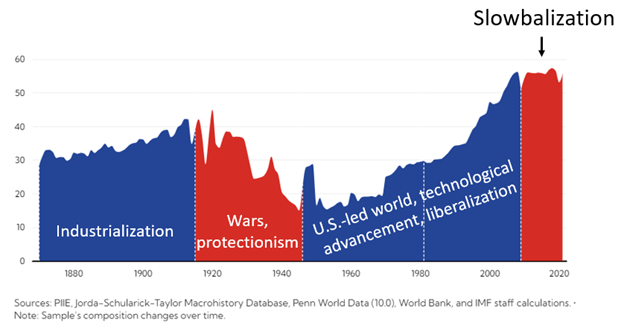

We’ve seen this movie before. After global trade consistently increased throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, thanks to the Second Industrial Revolution, it then took a dive, as World War I and World War II forced nations to be more self-sufficient.

But the absence of any major wars since 1945 has led to the greatest growth in global trade and economic output in the history of the planet. People all over the world benefited, becoming healthier, wealthier, and better educated. Technologies connecting us became cheaper, and countries could trade with very few barriers.

And in the late 1990s, when the internet took off, the result was globalization on steroids. You could do research in one country, source materials in others, produce a product in yet another, and then distribute it all over the world. Whatever device you are using to read this article was a product of the collaboration of multiple countries.

But such global collaboration is becoming more difficult. Since 2008, geopolitical tensions between the world’s largest economies have put a damper on relations, and the result has been “Slowbalization.”

Global trade might decrease, it might stay stagnant, but we are never going to see massive increases in global trade like we have in the past.

Those days are over.

At BCWM, we believe this trend favors increased investment in U.S.-based equities.

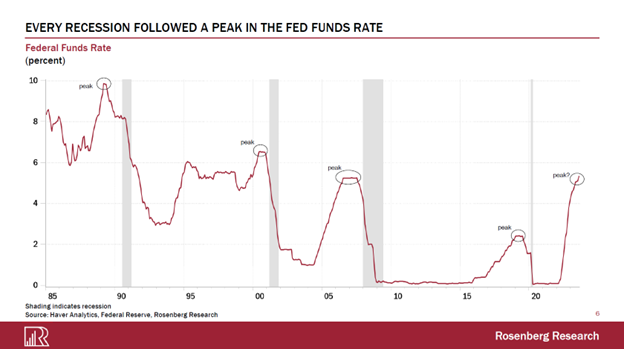

Last month we cautioned readers not to drink the Fed “Kool-Aid,” focusing solely on the data that shows our economy has been resilient, ignoring the ominous storm clouds on the horizon. The economic cycle almost always follows a similar pattern: inflation heats up, the Fed hikes interest rates to cool things down, inflation subsides, and the economy slows or shrinks (recession).

So, it wasn’t all that alarming last year when the Fed’s message was basically, “We’re killing inflation, the economy be damned.” But today the Fed wants to have its cake (lower inflation) and eat it too (no recession). Whether it’s Kool-Aid or cake . . . we are skeptical.

Why is that? Look at the relationship between the Fed’s previous rate-hiking actions and recessions.

The red line shows the “Federal Funds Rate,” the short-term interest rate controlled by the Fed. When the hiking stops and the Federal Funds Rate peaks, a recession (denoted by the gray bars) follows.

Which leads to the question . . . Has the current cycle peaked? We think so. And the market agrees. It’s likely that the Fed will start cutting interest rates in 2024. So, look out, because the economic cycle is undefeated, we know what comes next.

Bonds have become increasingly out of favor the last few months. However, when times get tough, investors will flock to safe-haven assets and bonds will prove their worth. And in the meantime, we still think bonds represent the best risk-reward tradeoff available.

This information is provided for general information purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax, or legal advice. Past performance of any market results is no assurance of future performance. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources deemed reliable but is not guaranteed.