Allegedly, the United States will soon run out of money. Unless Congress quickly votes to increase the amount of debt we are authorized to issue (aka the “debt ceiling”), our country will soon be a very large global deadbeat. The largest global deadbeat in the history of the globe.

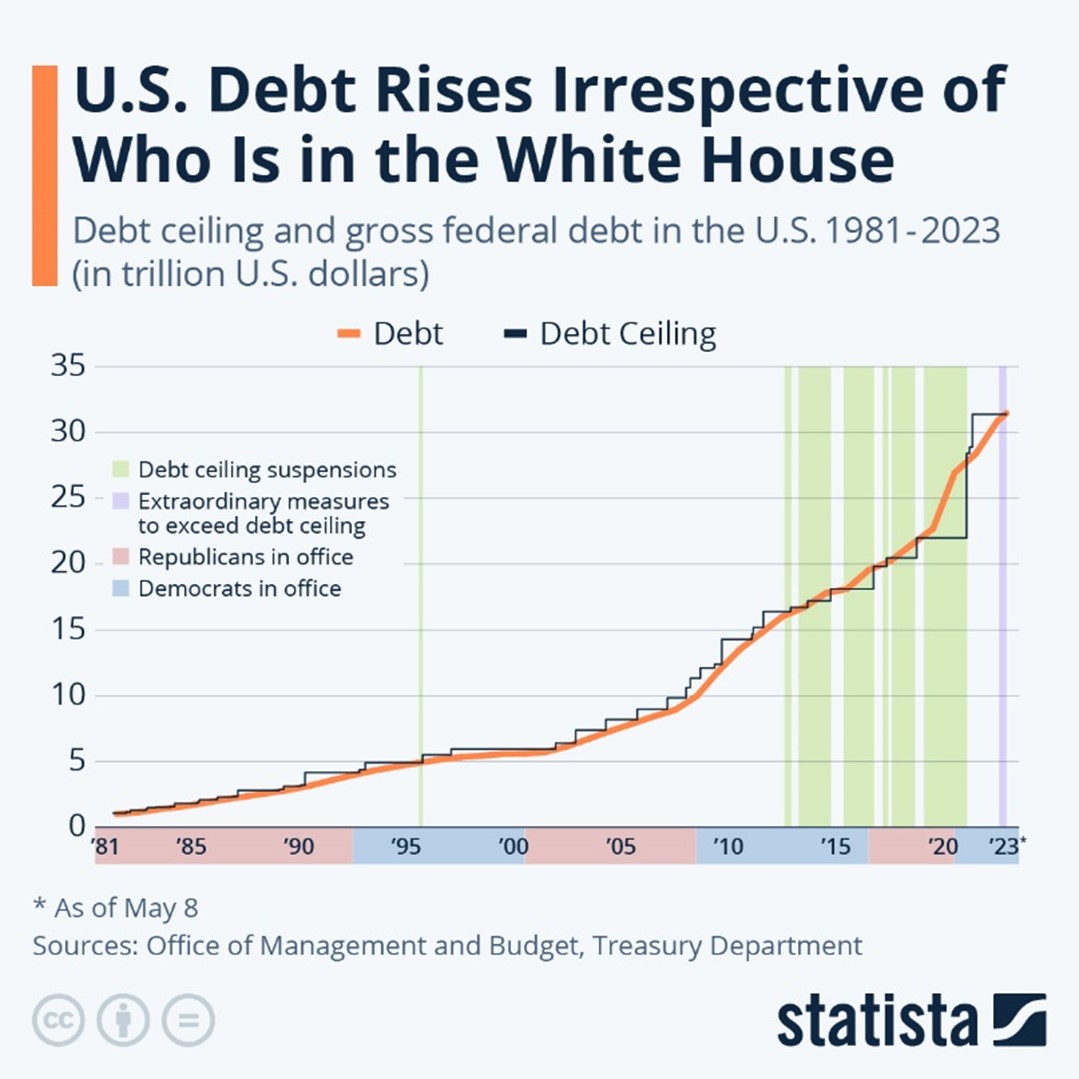

We say “allegedly,” because every time the U.S. gets close to running out of money, Congress votes to increase the amount of debt the U.S. can issue (or temporarily suspend enforcing the debt ceiling) . . . so then we technically don’t run out of money. In December 2021, Congress determined that amount to be $31.4 trillion.

We apparently have already hit that number (several months ago), and Republicans and Democrats have to get together in the same room to figure out how to make that a bigger number. We have no doubt that will eventually happen, but currently each side is having WAY too much fun blaming the other for not cooperating enough to make that a bigger number.

Since its introduction, in 1917, the debt ceiling has been raised over 100 times, irrespective of who is in the White House or who controls Congress. Say what they will, Democrats AND Republicans like to spend money.

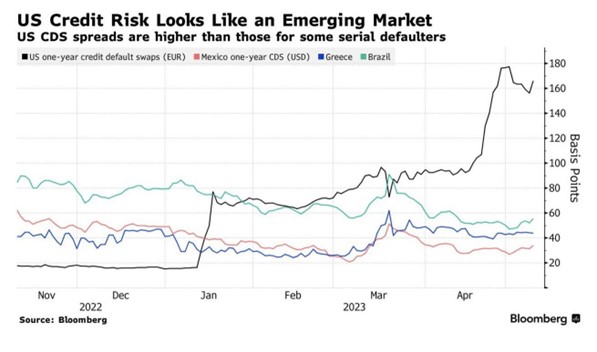

The markets are starting to make bets on whether or not this will happen. The cost of buying a one-year Credit Default Swap on U.S. debt (insurance that pays out if the U.S. defaults) is higher than a C.D.S. for Greece, Mexico, or Brazil.

For context, Greece has defaulted on its debt twice in the last eleven years. The United States has never defaulted on its debt.

The closest we have come to defaulting was the summer of 2011. From early July to early August that year, the S&P 500 fell more than 17%, presumably because investors were worried about a default (kinda like today maybe?). And Standard & Poor’s actually downgraded the U.S. government’s creditworthiness on August 5th, pretty much confirming what everyone was worried about.

Except the U.S. government did NOT default. They raised the debt ceiling and the stock market rallied 28% over the next twelve months. Average investors felt like idiots.

During that stock market drop of 17%, long-term U.S. Government Treasury Bonds (the bonds for the entity that was about to default) INCREASED double digits! Go figure.

If you want to take a couple of lessons from the summer of 2011, they are:

- Once the bad news has made its way to you, the markets have already changed their prices to account for the bad news. It’s too late to panic.

- The time to buy is when everyone else is in a panic.

We believe it is unlikely that a U.S. default will occur, and we are not positioning our portfolios for that possibility (although if one does occur, our portfolios would be expected to outperform the broader markets, as bonds and gold will likely increase in value).

However, the talk about the national debt is relevant to where our economy and markets are headed. The story hasn’t changed for years. And it’s very much one of demographics. As Baby Boomers continue to retire, they shift from being “contributors to” the economy to being “takers from” the economy. As a result, tax revenues will decrease and entitlement expenditures (e.g., Medicare/Social Security) will continue to increase. The real problem isn’t whether the U.S. raises the debt ceiling now, it’s how we plan to pay for all this spending over time.

The solutions are to reduce entitlements or raise taxes ¾ or a combination of both. Reducing entitlements is better for the economy, but less politically palatable.

____________________________________________________________________

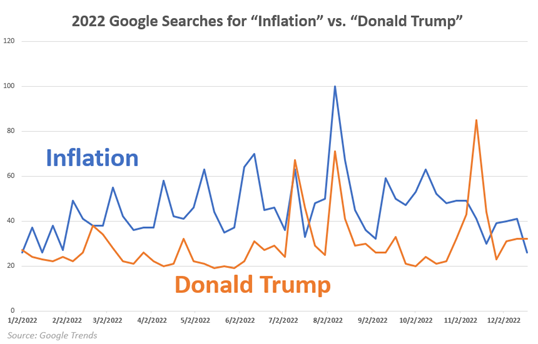

It was recently reported that the April Consumer Price Index (CPI), aka inflation, clocked in at 4.9%, which is way down from the 9.1% rate in June 2022, just ten months prior. Back then, inflation was the world’s most popular buzzword. Fears of high inflation (or runaway inflation or hyperinflation, take your hyperbolic pick) got everyone’s attention. Constantly. Relentlessly. It was a more popular topic than Donald Trump.

During that period, we repeated our view that inflation had peaked and it wouldn’t be long before it returned to more “normal” levels. And as inflation dropped each month, the buzz faded, and it was replaced with more exciting topics in the media.

We have not changed our tune. Inflation is coming down. And it’s becoming more boring by the day.

Measuring inflation might be even more boring. But there is one interesting quirk that is relevant to how we think about where inflation is headed.

When the government crunches the numbers, they include a measure of the change in housing prices (among other things). But unlike milk, the price of your house doesn’t change frequently, so economists must apply some scientific expertise to estimate the change in housing prices.

What do they do? They call a bunch of homeowners to ask them what they would charge to rent out their house. They call this “owners’ equivalent rent.” Seems . . . less than reliable. Seriously, do you have a clue what you could charge someone to rent your home? And do you think that number would be dramatically different next month? Or the next?

The truth is that this calculation usually does an okay job. But there are times when it does not. Right now, according to this method, housing prices are estimated to be up 8.1% from last year. However, alternative measures suggest that home price growth is about half that. And housing prices make up about one-third of CPI, so this can really move the needle on the reported inflation number.

Incorporating some more real-time data suggests that inflation was probably even lower than the 4.9% recently reported. And as we have repeated ad nauseam since last summer, we expect it to continue to decline.

The bond market agrees with us. The “break-even inflation rate” says that inflation is going to average about 2.25% over the next decade.

But that’s not very exciting, so don’t expect to read about it anywhere but here.

At BCWM, we are not worried about a debt ceiling crisis. We are not worried about inflation.

This information is provided for general information purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax, or legal advice. Past performance of any market results is no assurance of future performance. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources deemed reliable but is not guaranteed.