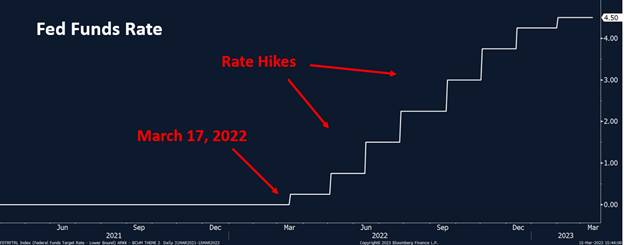

A year ago today, the Federal Reserve began raising interest rates to fight inflation. And since then, the Fed has raised rates eight times (a total of 4.5%).

Prior to this, we were in an environment where rates were held artificially low. And it was a wild world. Just like in 2008, when people were quitting their jobs to become house-flippers, in 2020/2021, people quit their jobs to become day traders or crypto “geniuses.” They bought “assets” like CryptoKitties, Digital Pet Rocks (and other NFTs), Meme Stocks, and the ARK Innovation Fund (to name a few).

Money was abundant, sloshing around the financial system, driving up prices so fast that it became a problem.

That’s when the Fed stepped in ¾ with the goal of maintaining healthy levels of unemployment and inflation. Unemployment hasn’t been a problem, but even if it was, officials at the Fed have made it clear that inflation is the bigger evil and they will stop at nothing to ensure they get a handle on prices. (After this week, they might be re-thinking that strategy.)

So, the Fed raised rates . . . again and again and again and again and again and again and again and again. This cycle of rate increases has been one of the fastest on record. The Fed has signaled it will continue to raise rates until inflation is brought under control. But this can have unintended consequences. Sometimes other things break first.

When you’re putting stress on a system, the rickety parts break first. We saw this last summer with cryptocurrencies, which, along with financial fraud, led to the collapse of FTX. Last week, the stress hit a bank in Silicon Valley appropriately named Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

What happened?

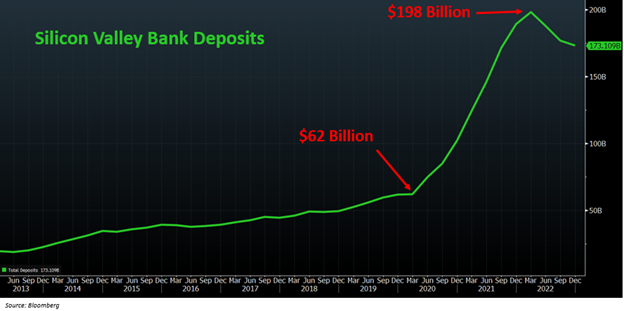

Silicon Valley Bank’s customers were (predominantly) tech startups and venture capitalists. As such, in 2021, they had a LOT of money. Remember 2021? People were throwing cash at tech companies. And those tech companies parked much of that excess cash at SVB. The bank’s deposits grew from $62 billion at the start of 2020 to almost $200 billion two years later.

That sounds like a good thing, but it created a problem. Typically, banks earn profits by taking deposits/cash (which pay a low interest rate) and making loans (which charge a higher interest rate). But SVB couldn’t find borrowers as fast as they were accumulating deposits. So, they had to invest the money elsewhere. They decided to invest most of it in safe U.S. government-backed bonds.

Short-term bonds were paying next to nothing at the time, so to earn a higher return, they bought longer-term bonds, a strategy that put them at the risk of rising interest rates . . . which, of course, happened almost immediately, and their bond portfolio lost a lot of money (on paper).

But thanks to the way the banking system works, this “paper loss” does not usually result in a bank failure. Regulators allow them to ignore the loss, because eventually the bonds will pay back in full at maturity. SVB wasn’t going to sell the bonds if they were up and they weren’t planning on selling them because they were down (turning the “paper loss” into a real loss).

Plans change.

All of a sudden, this large paper loss that had been brewing for months spooked depositors, fear quickly spread via social media, and a good ol’ fashioned bank run ensued. Customers pulled their money from the bank, but . . . SVB didn’t have the cash immediately available . . . so, they had to sell the bonds (at an inconvenient loss).

The paper loss became real and the bank collapsed.

If you feel like you’ve heard this story before, you probably have. Every Christmas.

There are differing opinions on how this bank failure should be handled. Should all depositors be made whole even though some deposits were over the $250,000 FDIC-insured limit? To the average American, a “depositor bailout” feels like we are using taxpayer dollars to make the rich wealthier.

But one could argue, and Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine does, that “The point of a bank deposit is that you shouldn’t have to worry about it, and that it is a failure of bank regulation if depositors of any size have ‘to actually give a moment’s thought to the riskiness’ of a bank.”

Forcing someone with $2 million to go to eight different banks just to remain under the $250,000 limit seems like an unnecessary waste of everybody’s time.

Ultimately, the U.S. government determined that not making all depositors whole would have a more harmful effect on the banking system (additional panic and bank runs?) and the economy.

However, the shareholders of SVB will get nothing (stock was trading at $333/share on February 2nd) and upper management will have to find new employment.

Silicon Valley Bank was certainly not as rickety as the cryptocurrency market. But it was one of the more rickety members of the regional banking system. Is the Fed done trying to break things? We will find out next Wednesday if it will continue with rate hikes.

Meanwhile, it is our opinion that this “banking crisis” is nothing close to what we experienced in 2008–2009. We are not concerned that this will turn into some toxic financial virus for which there is no antidote. In the Great Financial Crisis, the world was inundated with debt (primarily sub-prime mortgages) that was initially considered “investment grade” (some rated AAA) but that quickly became worthless . . . leaving the whole world holding the bag.

This is nothing like that. Banks are not experiencing credit risk. They are just experiencing what we call “duration risk” . . . combined with a dash of stupidity.

At BCWM, we continue to see a slower U.S. economy and lower interest rates (they have fallen precipitously this month, caused by the aforementioned problems). We are not changing our investment strategy. Although, if interest rates fall significantly lower, we may lighten up our investment allocation to long-term government bonds.

This information is provided for general information purposes only and should not be construed as investment, tax, or legal advice. Past performance of any market results is no assurance of future performance. The information contained herein has been obtained from sources deemed reliable but is not guaranteed.